Factober

So it's October, and not only it is the month of Oktoberfest, but also that of Inktober. The concept of Inktober is the following: there is an official list of words - one per day - (although anyone can create its own) and artists who want to can make a drawing about this word. The idea is to force themselves to draw each day to improve their skills (and surely also for fun).

I don't know how to draw. However, I do like science and learning stuff. Also, I need to practice writing for my upcoming Ph.D. Thus I came up with an idea: Factober.

I will every day and for each word present a fact or answer a question related to it, in the style of scientific writing.

Note that I am a physics student and because of the diversity of words, I may find myself writing about things I am learning on-the-fly and thus may contain some inaccuracies.

Moreover, there is a non-zero probability that I give up at some point.

Facts

1. Dream

Sleep have been shown to be essential for the brain to function. The litterature reports a deterioration of performances in many different cognitive tasks during sleep deprivation [1].

In particular, sleep plays an important role for learning and for the memory [2,3].

What I (briefly) want to focus on here is more specifically the role of dreaming for thoses tasks.

An idea from F. Crick and G. Mitchison in 1983 is that dreaming is a way for the brain to explicitly unlearn (and not just forget) undesirable information, motivated by the fact that the dreams are remembered only when we wake up in the middle ; and that we need effort in order not to forget it [4].

This idea echoes a recent learning algorithm for Artificial Neural Networks developed by G. Hinton: the Forward-Forward Algorithm [5].

The common algorithm to make neural networks learn is Backpropagation: the network is fed with some input, and the output is compared to the expected output. The error computed goes backward in the network to update each synapse's weights (i.e. the network parameters) according to the error's derivative in order to minimize it.

However, the signal propagating backward makes this algorithm not biologically plausible: we do not observe anything alike in the brain.

What proposes the Forward-Forward algorithm is to propagate the signal forward, with positive input data, which would typically represent the data we process when awake ; and then propagate the signal forward again, but with negative data, which would typically represent the data we create and process when dreaming.

But why would we look for a bio-plausible learning algorithm, when we already have one which is obviously powerful (c.f. ChatGPT and other LLMs)?

Because the brain is a very energy-efficient machine: it consumes only about 20W while training those LLMs required supercomputer for a total energy of 1000kWh, that is, the energy the brain uses in six years [6].

However, the theory of unlearning has not proved to be what really happens and other theories exist: more research is needed to better understand our brain.

This is not because a theory may be wrong that brain-inspired computing must not consider it: the power of current AIs relies on an over-simplified model of our neurons and on an invalid learning process.

Who knows, maybe the future AIs will dream of electric sheep?

2. Spiders

We talked yesterday of taking inspiration of the human brain for computing. But computer science is far from the only field to take inspiration from nature. Indeed, natural structure, materials, and machineries are often the result of millions of years of evolution, which inevitably leads to the most efficient solutions.

Another wonder of the nature are spider webs. They are high-performance structures unmatched anywhere else. For comparison, we define the toughness of a material as the area under its stress (i.e. strength) v.s. strain (i.e. extensibility) curve until it breaks. This quantifies the energy required to snap the material. The silk of the Areneus, a species of spider, has a toughness of 150 MJ.m-3 versus 25 MJ.m-3 for carbon fibre [7].

The development of such a high-performance silk can be understood as it is the only survival advantage of spiders: they are prone to physical damage, breathe through lungs, constantly need high humidity, are wingless and their legs buckle when overused [8].

However, the structure and geometry of spiders web have not been investiguated until 2016, when scientists studied their acoustic properties [9]. They show that spider webs could be used to damp low-frequency vibrations, and that tuning their structure allows this property to be fine-tuned.

In a crystal, a regular arrangement of atoms, waves cannot propagate freely. Whereas in the vacuum, all electromagnetic waves (i.e. light) propagate at the same speed, in a crystal, their speed depends on their wavelength: \( v = f(\lambda) \). This is the dispersion relation.

The exact same applies to mechanical waves, such as sound waves, and their speed is a function of their frequency. In particular, it may happen that the speed of a wave is not defined for a range of frequencies. Equivalently, such a wave cannot propagate in the structure and this is called a bandgap.

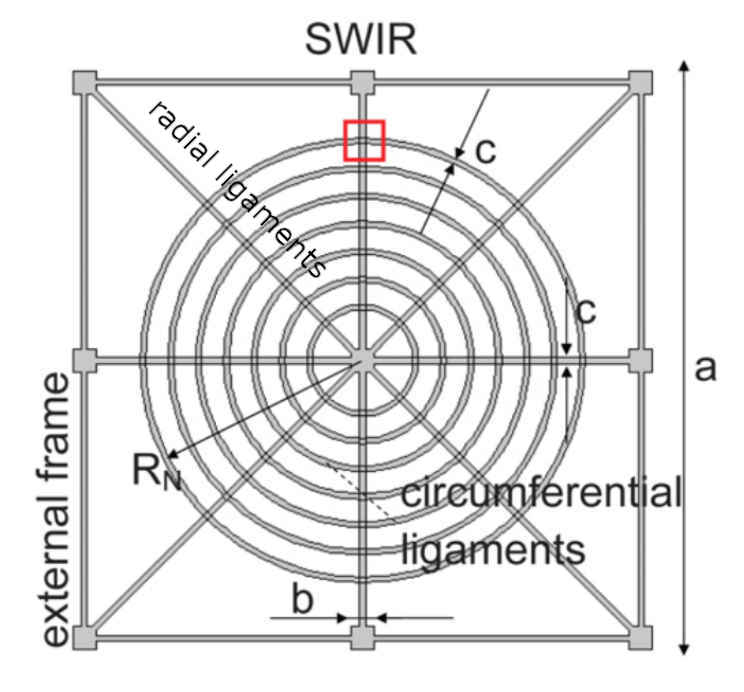

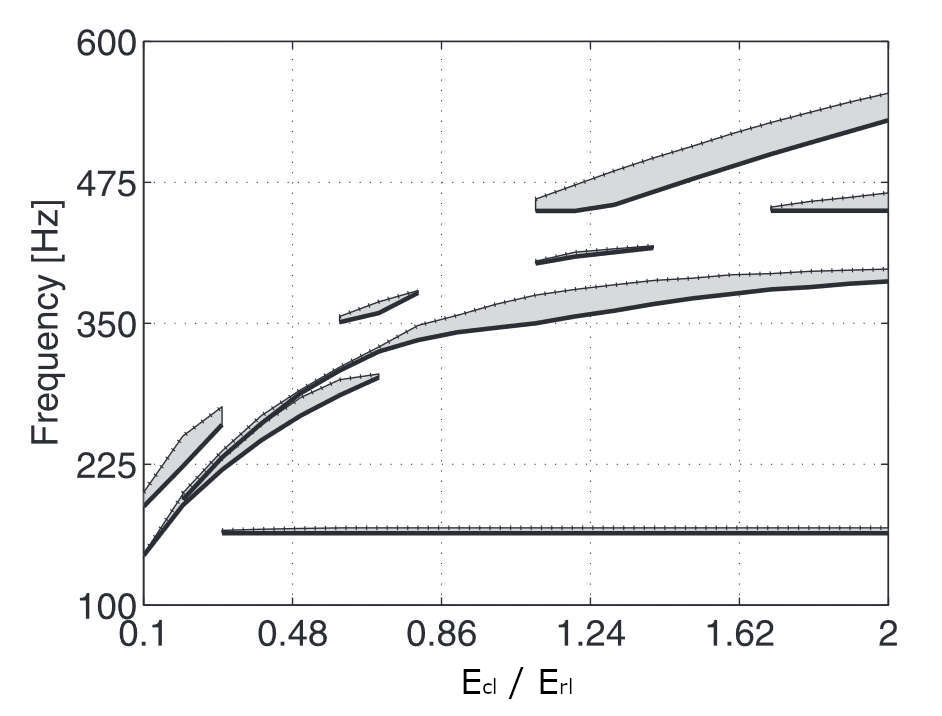

By tuning the ratio of stiffness of the circumferential ligaments \( E_\mathrm{cl} \) over that of the radial ligaments \( E_\mathrm{rl} \), they successfully tuned the band gap frequencies:

They conclude that this study could lead to the development of functional spider-web-structure based materials, for instance to protect suspended bridges from earthquake.

3. Path

I dont have much time today, so here are the key points, I will elaborate more this week end, hopefully.

Lagrangian \( \mathcal{L}(x, \dot{x}) \): basically the difference between the kinetic energy and the potential energy of a system.

Action \( \mathcal{S}[x(t)] \): the integral of the Lagrangian over time for a given path \( x(t) \).

Stationary-action principle: this principle states that classical mechanics always choose the path with a stationary action, i.e. the path with a minimal action.

Modified from Wikimedia Commons.

Path integral formulation: in the quantum world, we use probabilist tools to describe the objects, and their position. The probability for a particle to be at position \( x_f \) and at time \( t_f \) knowing that it was at \( x_i \) at the time \( t_i \) is written as \( \langle x_f, t_f | x_i, t_i \rangle \). Dirac stated that the probability was analogous to \( \mathrm{e}^{\frac{i}{\hbar} \mathcal{S}[x(t)]} \) [X] ; Feynman will show in its thesis that they are proportional [X]: \[ \langle x_f, t_f | x_i, t_i \rangle = \int \mathcal{D}x(t) \mathrm{e}^{\frac{i}{\hbar} \mathcal{S}[x(t)]}\]

As a comparison with classical mechanics, where we take only a definite path, in quantum mechanics, we integrate over all possible paths: an interpretation is that the quantum particle explore every possible paths, i.e. not only the red from the previous figure, but also the green ones.

X. Already the end

I gave up...But here are the subjects I wanted to talk about, if ever I find the time & motivation to do so:

- Dodge: Talk about boids and how they manage to not collide with each other

- Map: About NP-complete problems mapping and how to map 3-SAT (algorithmic problem) to an Ising problem (physics problem) in order to solve the former

- Golden: What it would physically/chemically mean to turn lead into gold

- Drip: Osmose pressure and how it should be considered not to explode your cells when you are on a drip

- Toad: Tchernobyl frogs became black because of natural selection and natural protection of melanin against radiations

- Bounce: not sure, maybe how to compute pi with bounces but 3Blue1Brown already did it

- Fortune: dont know

- Wander: wandering with your mind: the science of boredome

- ...

- Frost: negative absolute temperatures are hotter than absolute zero

References

- [1] Alhola, P., & Polo-Kantola, P. (2007). Sleep deprivation: Impact on cognitive performance. Neuropsychiatric disease and treatment, 3(5), 553–567.

- [2] Diekelmann, S., & Born, J. (2010). The memory function of sleep. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 11(2), 114-126.

- [3] Maquet, P., Schwartz, S., Passingham, R., & Frith, C. (2003). Sleep-related consolidation of a visuomotor skill: brain mechanisms as assessed by functional magnetic resonance imaging. Journal of Neuroscience, 23(4), 1432-1440.

- [4] Crick, F., & Mitchison, G. (1983). The function of dream sleep. Nature, 304(5922), 111-114.

- [5] Hinton, G. (2022). The forward-forward algorithm: Some preliminary investigations. arXiv preprint arXiv:2212.13345.

- [6] Marković, D., Mizrahi, F., Querlioz, D., & Grollier, J. (2020). Physics for neuromorphic computing. Nature Reviews Physics, 2(9), 499-510.

- [7] Gosline, J. M., Guerette, P. A., Ortlepp, C. S., & Savage, K. N. (1999). The mechanical design of spider silks: from fibroin sequence to mechanical function. Journal of Experimental Biology, 202(23), 3295-3303.

- [8] Vollrath, F. (2003). Web masters.

- [9] Miniaci, M., Krushynska, A., Movchan, A. B., Bosia, F., & Pugno, N. M. (2016). Spider web-inspired acoustic metamaterials. Applied Physics Letters, 109(7).

- [X] Dirac, P. A. M. (1933). The Lagrangian in quantum mechanics. Physikalische Zeitschirift der Sowjetunion, 3, 312-320.